Published on Nov 17, 2022

The author of this blog, Kayla Brown, is the Development and Communications Manager with the Network for College Success (NCS). She is responsible for supporting fundraising activities and drafting informational and marketing materials. In her spare time, she enjoys reading historical fiction novels and writing poetry.

I joined the Network for College Success during a time of much heartache and stress. The COVID-19 pandemic hit communities hard, and the world was still reeling from witnessing the murder of George Floyd. As a Black woman, my heart was heavy. At the same time, I was starting a new position at a project housed at the University of Chicago. Long before my start date, I was conditioned to compartmentalize my emotions in the far corner of my mind. I learned long ago that my whole self was not meant to be brought into the workplace. I was unprepared for how NCS would flip this narrative and challenge me.

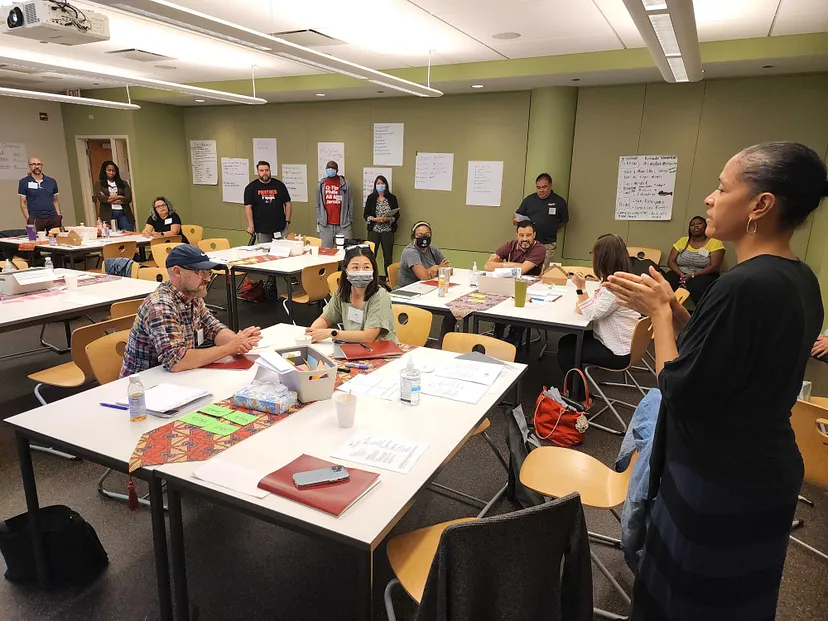

Although we do not directly serve students, NCS partners with high schools to co-create safe and equitable conditions for students that will ultimately result in positive academic outcomes. NCS is not afraid to name the harmful systems that adults can unknowingly perpetuate and how they create obstacles for students to thrive. Many of these systems are rooted in racism and white supremacy, disproportionately harming Black, Indigenous, and Youth Of Color (BIYOC). To take on this transformational work, NCS provides professional learning communities and one-on-one coaching for adults. More so, we do not ask our partners to do work we don’t do as staff. Last summer, I was asked to join one of our professional learning workshops as a participant, along with teachers, principals, and administrators interested in taking on antiracist equity work.

The Equity-Based Leadership (EBL) workshop serves as a learning space for participants to examine their identity in relation to leadership and to explore how “the skin they are in” impacts the communities they are part of. The goal is for participants to learn antiracist practices that can help them lead transformative work in their respective spaces–ultimately to improve student experiences.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to have participated in EBL. After my four days at the workshop, I walked away with three ideas that I feel will support me to lead for equity and show up as my full self in every room I’m in.

Image

#1 We must look on the inside

Per the NCS Equity Stance, which staff members drafted 5+ years ago, “transformation happens from the inside out.” Building off this idea, EBL took its participants on a journey to examine our identities and experiences. NCS facilitators named that it’s crucial to start with race when thinking about one’s identity. Although there is more to people than their racial makeup, when it comes to living in the United States, “race is the strongest predictor of how you experience this country.”

Speaking from firsthand experience, my Blackness is at the forefront of my mind from the moment I awake to the moment I fall asleep. I am constantly aware of this part of my identity and how it impacts how I relate to others. Although I have pride in my identity as a Black woman, I recognize there is pain that exists there, too. I can remember being discarded, ignored, or harmed because of my race. These feelings have caused distrust to live within me, especially towards white people. I become guarded or shrink myself to take up less space, specifically when I’m the only Black person in the room. EBL helped me understand how unexamined parts of identity can become “baggage” and result in harmful actions to yourself and others. If we examine aspects of ourselves instead, it can lead to liberation.

Our emotions are tied to our identity. As an equity leader, it’s essential to acknowledge them within our teams. White supremacy culture tells us that it is not OK to be emotional in certain spaces. Before coming to NCS, I accepted that it was best to assimilate into a culture (usually predominantly white) so I could succeed or operate safely unnoticed. Additionally, family and friends advised me to keep emotions and sensitive topics out of the workplace at all times in order to not draw attention or be labeled a “troublemaker.” Young people are often forced to adapt to the inequitable and outdated systems in schools for this very reason. Yet, if we do not have a healthy way of managing our emotions, it can be harmful to our minds and bodies. During this workshop, we discussed how we, as adults, must come to terms with our own distress and understand our own social-emotional landscapes. We cannot lead with equity in our schools or respective spaces if we cannot see the needs and feelings of others or if we are carrying unchecked baggage. In order to progress in my equity journey, I will continue to examine how situations around race have hurt me and impacted how I interact with those around me.

#2 We must remember the past

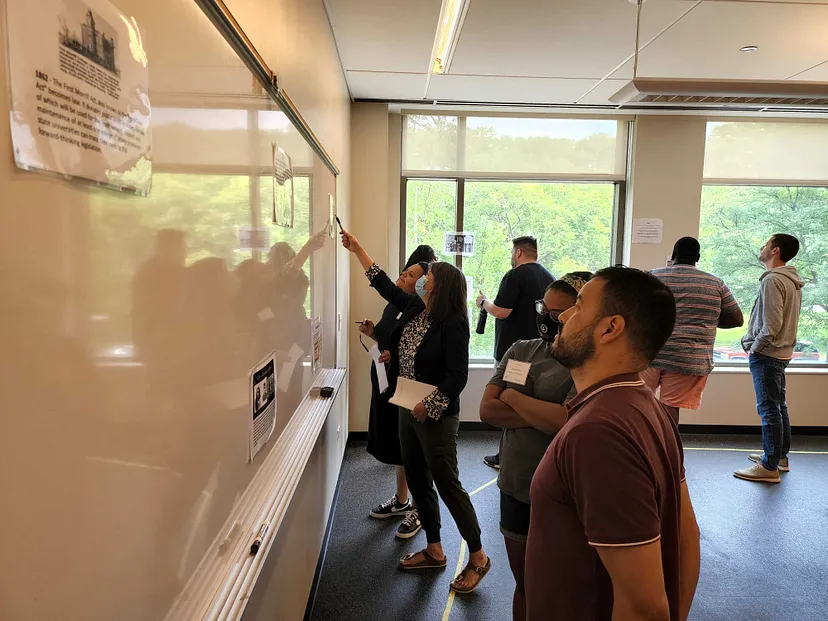

A question was brought up to us, “Was American education and schooling currently serving our students? If not, why?” Our EBL facilitators made it clear that during our workshop, we would be closely examining race; “Racism is deeply embedded in the institutions in this society, leading to inequities.” One of the most striking ways we explored this concept was by going on a historical timeline walk. In another room, with a partner, we walked through a gallery of images that marked times in history when racist and inequitable practices were put into place in US education systems. Notably:

1864: Congress makes it illegal for Native Americans to be taught in their own language. Children are taken from their families and put in boarding schools where they are forced to speak/learn English, give up their Native names, and get rid of their traditional clothing.

Late 19th century: Children of Asian descent were repeatedly banned from joining white schools in San Francisco. The reason given: “self-preservation.”

1931: The Lemon Grove Incident–Principal Jerome T Green, directed by an all white school board, allowed everyone except Mexican children into his school. He turned them away at the door and directed them to a smaller, old building. This is an example of popular discrimination practices at the time that were labeled as “Americanization.”

1957: As nine Black students from Little Rock, Arkansas attempt to enroll in an all-white high school, Governor Orval Faubus sends the National Guard to physically stop them. Additionally, the students endured severe physical and verbal harassment from white parents and students.

These are just a few examples of how the US education system promoted white hegemony and instilled “whiteness” or “Americanness” as the baseline/normal culture. In a system such as this, Black and Brown people cannot bring their whole selves to spaces or feel safe doing so.

Image

I can still vividly remember my time as a young Black girl attending a St. Louis Public Elementary school. I can remember the classrooms being mostly made up of Black children. Nine times out of ten, the teacher was a white female. Years later, when I entered middle school and high school, I transferred to a private school that was predominantly white. This school was larger, cleaner, and had way more resources than my old school. This school was also in a much wealthier neighborhood surrounded by malls, boutiques, and restaurants. It was night and day. The segregation was clear yet unspoken.

All I knew at the time was to “be good.” Be the good Black student who gets involved, gets good grades, and will get into a good college. Do not give anyone, particularly white people in positions of power, a reason to call me out. Follow the rules and become invisible. I now see that “being good” meant nothing about myself or my values. In fact, it was meant to erase everything that made up my being in favor of compliance, silence, and order. There is no place for these values in my equity leadership. I cannot make progress in antiracism work if I’m not bringing my whole imperfect self to the table.

EBL encouraged us to not only look at harmful policies and rules in “the system”, but to look at ourselves and past behavior. Educators and school leaders in the workshop reflected openly about how past actions on their part may have harmed children. Were there rules or compliances they followed that contributed to perpetuating inequitable and harmful practices? It was clear to all of us how our inequitable education system has (and continues) to fail BIYOC.

In the NCS Postsecondary Toolkit, research and data show that students that have positive experiences in schools are more likely to achieve postsecondary success. To ensure this can happen, students must feel safe and have their identities and experiences be seen and valued, especially by the adults in the building. We cannot rewrite our past or our country’s, but we must take on the responsibility of disrupting inequities–for the sake of children today and tomorrow.

#3 We must take action together

Early on in the workshop, we collectively defined equity and shared beliefs about why it was important to have equitable practices in schools. It was clear that EBL was meant to be not just a personal, but a collaborative experience. “It takes a village” became our mantra for the whole week. We were first asked to do some reflective work about ourselves. I had to address my identity as a Black woman and acknowledge what comes with that. Afterward, participants shared their identities with each other. Through this, we could see where our stories overlapped and/or differed. But we all had the same goal in mind; we wanted a different world for our children and for ourselves. We wanted justice, safety, and healing. Making positive systematic change cannot be done alone. We need to uplift each other, have tough conversations, and take action steps towards meaningful shifts.

On the final day of EBL, we held a commitment ceremony. NCS facilitators and the participants sat in one large circle, symbolizing the unity and connection built around this work. We promised ourselves to continue the work done in EBL outside of the space. At this moment, I didn’t care that I was not an educator or principal. I was part of a community. I was a member who, like others in this room, had gone through a significant change in a matter of four days. In this space, we recommitted ourselves to taking bold new actions to fight against inequity together.

Final Thoughts

Many times during this workshop, I was in awe of the dedication of the adults in the room. Students were at the forefront of each and everyone’s mind. There were a handful of times when I looked around and saw adults speak frankly about what their BIYOC need in their schools and what action they will take. I could feel the young Black girl in me, who once felt that adults did not care or notice, feel seen. My hope is that all children can experience that same feeling. I am honored I was able to be in the same room with the educators and school leaders at EBL, and I cannot wait to see what we can accomplish together.