Published on Mar 16, 2023

The author of this blog, Rachel Castro, is the Development Associate with the UChicago Network for College Success. She supports grant writing and reporting initiatives.

As a Latinx child of immigrants, I noticed early on that school systems were built for and favored students whose parents knew how to navigate them. I grew up in predominantly white schools alongside peers who had caretakers with a college education, time to help their children with school assignments or volunteer in classrooms, and the resources to advocate for their children’s needs around test taking or extra help. They had been born into the English language and had lives that resembled my teachers’. Without those entries, my experience as a student was isolating.

As part of their practice, my teachers considered classroom behavior when grading students’ work. Grades could be used as a punitive measure to alarm students into aligning their behaviors with each teacher’s values. They often felt subjective and difficult to assess. I eventually learned to assimilate and take few risks.

A couple of months into my time at UChicago Network for College Success, I attended a presentation by team members on equitable grading policies based on an accompanying text that informed much of their thinking and what those policy changes looked like within Chicago Public Schools (CPS). I was so excited by the idea of school leaders addressing outdated and punitive grading systems. To learn more, I asked NCS coaches Beth Brown and Octavio Casas questions about their work with our partner schools and learned how grading practices grounded in equity can make the student experience less nebulous and more joyful.

Rachel: Hi, Octavio and Beth. Can you each tell me a little about yourselves, your roles at NCS, and your experience with CPS expectations around grading and equity?

Octavio: I am one of the leadership coaches with NCS and my experience with grading has been unique. I did start with Chicago Public Schools as a teacher and ultimately moved into a school administrator role, but in both cases I was always very much interested in not just my students’ learning but also how to capture their learning in a way that makes sense for my students.

What I found out is that my own experiences with grading as a student impacted how I showed up as a teacher. I also realized that there were some similarities and sometimes some differences with how I approached grading and how my colleagues approached grading. That shifted me into an inquiry mode–really thinking about: “How am I serving or not serving my students and my communities?” As an administrator, I had an opportunity to really engage teachers in conversations around grading expectations.

Beth: I am the impact manager with NCS and similar to Octavio, I started as a teacher in CPS and then moved into school leadership. As a teacher I, too, noticed differences in the ways that teachers approached grading and how we gave grades to students, whether it be from the types of assignments and tasks that we were giving to how those things were weighted within our grade books. There were a lot of differences and inconsistencies in grading.

Then, when I moved into school leadership, my school, as part of the IB programme, was required to design a school-wide assessment policy. Through that process we had a lot of conversations around equitable grading and assessment, and what that should look like across classrooms within the school.

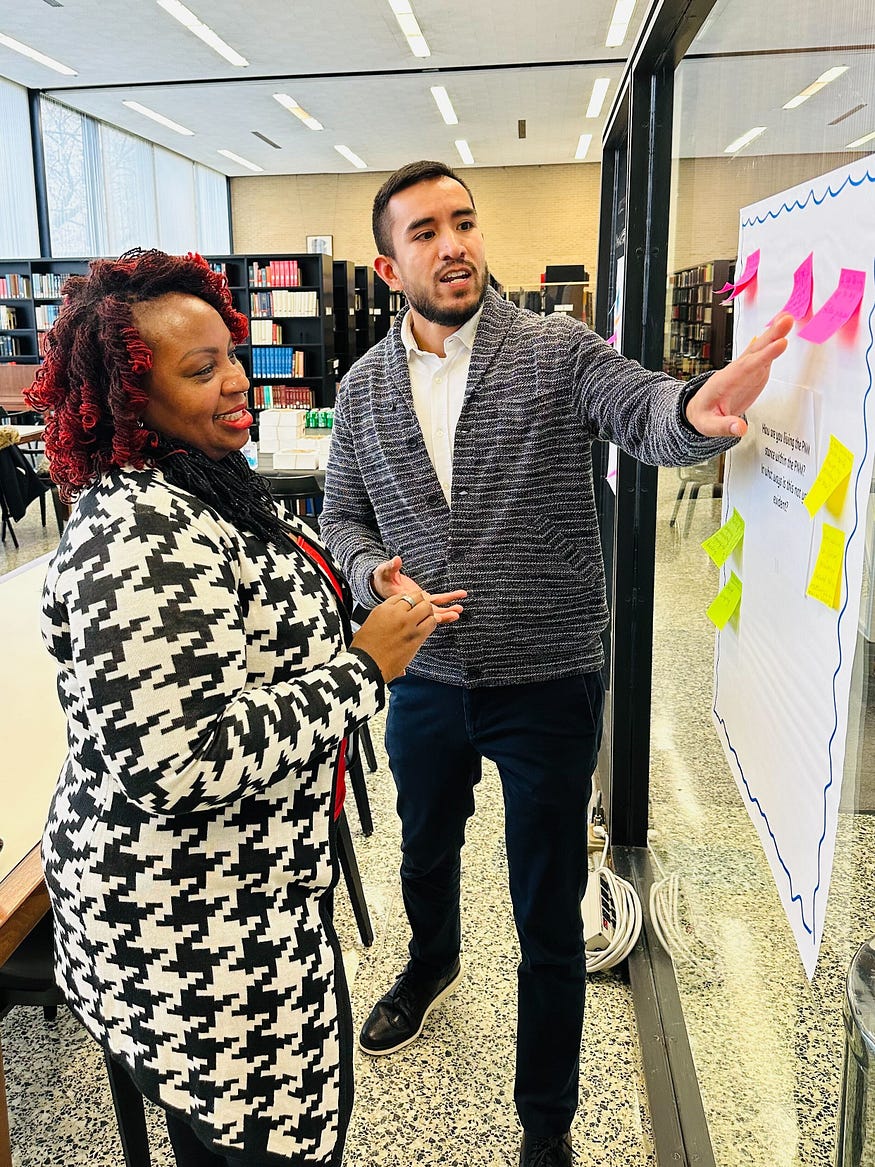

[Octavio Casas, Leadership Coach, and Dr. Kimberly Hinton, Deputy Director, Partner School Network]

Rachel: A few years ago, the Chicago Public Schools district and Chicago Teachers Union established grading guidelines rooted in equitable grading practices. What do those grading guidelines include and what texts or resources supported that work?

Octavio: CPS brought together educators from the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) as well as administrators from CPS to answer in part: “How can we best support students with grading and develop common grading expectations that best serve our kids across the district?”

From that conversation came the Professional Grading Standards and Grading Practices Guidelines for CPS teachers. As a principal, this clarified a few things for me and my team.

Beth: The text that was used to support that work is “Grading for Equity” by Joe Feldman. Myself and three other NCS coaches are currently using this book in our Freshman Success for Equity Improvement Network (FS4E) as a focal text to support the work that our partner schools are doing around Freshman Success. Essentially, they are testing instructional practices aligned to Joe Feldman’s pillars around accuracy, bias resistance, and motivation in grading.

We began using this book because last year we noticed that equitable grading practices were coming up as a theme across our convening spaces. When we got to the end of the year, it was important to weave equitable grading into the work that we were doing around developmental relationships as another way to engage more deeply with students.

Octavio: The guidelines talked about and set out expectations around the frequency for when grades should be entered and how grades should reflect a balanced and fair representation of students’ performance. There was also language around how teachers could use categories and weights to capture student learning and academic growth and language around making sure that grades were aligned to standards and objectives. Finally, there was also language around how some grading practices may differ according to specialty programs that we have across our district such as IB, gifted, Montessori, and other programs.

[Three Pillars of Equitable Grading Practices (Adapted from Grading for Equity by Joe Feldman)]

Rachel: What do Joe Feldman’s pillars of equitable grading look like in practice? And what questions are partner educators asking as a result of that framework?

Octavio: Our coaches, myself, and our teacher leaders were often in conversations where grading came up. They’re part of a larger conversation that we have with teachers around equity. In alignment with the accuracy pillar, for example, a question that might come up is: “Why is it important for teachers to have transparent and accessible grade criteria for students to be able to calculate their own grades?”

We want students to be very aware of where they are with learning, partially so they can take ownership of their learning but also to better understand the celebrations and opportunities for learning that still exist. We believe students are agents of change and they have the power to impact their learning and grades. We don’t want grading to be a mystery, and we want to make sure that it actually reflects their learning.

When I think about bias-resistant grades in conversations I have with teachers, it often requires us to examine our assumption about grades–our assumption about what students can and can’t do and also our assumptions about what we believe education should be. These are questions that allow us to open up a dialogue with teachers and really come back to this question: “Are we best serving our students? If not, what shifts do we have to do as adults to better serve them?”

And then, finally, a word on motivation. A question that might come up with teachers is: “How can our grading systems reflect and reward academic growth as opposed to solely immediate mastery?” Or: “What are examples of grading policies that are intrinsically motivated and not extrinsically motivational or punitive?” We want classrooms to be safe spaces where failure isn’t seen as something that’s negative or a final outcome. But how do we use failures as learning opportunities? Students should be motivated to be able to do well and they should be able to have multiple opportunities to succeed.

Rachel: How does NCS support our partner schools with equitable grading? Which new grading practices are school teams trying out in their schools?

Beth: In our Freshman Success for Equity community we are testing three different change ideas across our 11 schools:

Some teachers in our network are testing an accuracy pillar strategy of weighting more recent performances instead of averaging grades over time. They’re working to teach students specific skills, retest them, and replace lower grades with higher grades instead of averaging grades over time.

Teachers that are engaged in testing the bias-resistant practice are grading based on student work and not the timing of the work so, essentially, they are lifting any penalties that students may have received previously by turning in work late.

Teachers in schools that have chosen the motivational practice are creating a community of feedback among students. These schools are working on increasing peer to peer feedback opportunities for students in their classrooms.

Rachel: How has this work around equitable grading practices served as an entry point or served in tandem with the equity work taken up by our partner schools?

Octavio: I believe that grading practices in some cases are just the tip of the iceberg or only a piece to a much larger puzzle. When we talk about equitable grading practices, really, we are centering equity. What are the practices and structural shifts and changes we need to make to better serve our young people? Often it’s our most marginalized students–Black and brown students, ELL learners, diverse learners. It is an entry point and there is a lot more work to do. There’s work that is structural; some of it is external to the school but some of it is also internal within the school that people have a locus of control over.

I think there is amazing work happening at our partner schools around what it means to listen and respond to students’ voices and experiences. There’s also intentional work happening around learning about the conditions that support creating communities. Some of our schools are talking about student discourse and making sure that students are taking up rich conversations to not just excel and learn and grow within the classroom, but also to bring some of those skills outside the classroom.

Beth: When I think about the conversations that myself and colleagues are having with our coachees across the network, they are anchored in equitable grading as a focus to our freshman grade-level improvement work. Similar to what Octavio mentioned: grading for equity is an entry point into coaching conversations. These conversations are happening alongside other conversations about transformation, collective efficacy, and freshman success as a whole.

Rachel: Speaking of student success as a whole, including outside the classroom, what impact do you hope these grading practice changes will have on educators and students?

Octavio: Fundamentally, I hope these and future grading policy changes transform how our students experience schooling. I’m hoping educators and administrators work together to create a greater sense of transparency about what grades mean for students and families. I hope that this inspires all adults to really look inward to see what ways they are serving students and really take a critical lens at examining what structural policies need to be examined to create more equitable practices schoolwide.

Beth: Our network has an aim to increase the proportion of Black and Latinx male students achieving a 3.0 or higher GPA. I hope this work will have a positive impact on that aim, in addition to transforming classroom experiences and academic outcomes for 9th grade students across the network. It also makes me think of our goal to create deep and joyful learning experiences for all students. Ultimately, I hope the work makes an impact on this aim — for both students and educators.

Octavio: Shifts in adult practices are a means but not an end. Yes, students are having transformed educational experiences but we also want to see ongoing excellence in outcomes. We are not just talking about passing classes and graduating, but rather striving for and reaching our full potential and graduating feeling confident and authentically prepared for life after high school.

Rachel: Thank you both for introducing us to this work! Do you have any calls to action for readers since many of them may also be educators?

Octavio: My call to action is to engage other educators in this conversation with an open mind, to tap into their own curiosity and explore how others are taking up more equitable or antiracist practices in their classrooms.

Beth: Reflect on where you are and commit to making one small change in practice to deepen equitable grading in your classroom. The work is ongoing, and can be challenging, but the rewards are worth it.